Beverage alcohol compliance basics: The three-tier system, product registration, and taxes

Wine, beer, and spirits have been sold in the United States for hundreds of years. However, the landscape changed significantly following the repeal of Prohibition in the 1930s. With laws and regulations at the federal, state, and local levels, beverage alcohol products are one of the more highly regulated products in the U.S.

Whether you’re currently a producer or importer, or are just now considering entering the industry, this whitepaper will give you some basic background and guidance on what it takes to not only become, but remain, compliant.

After reading this guide, you’ll:

- Know how beverage alcohol regulation got started

- Understand what the three-tier system is

- See where your business fits into the beverage alcohol ecosystem

- Learn the main components of beverage alcohol compliance

- Discover the different taxes on alcohol products and who needs to pay them

A quick history of the U.S. beverage alcohol system structure

Prohibition was ushered in with the 18th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, passed in 1919. After multiple challenges throughout the 14 years of Prohibition, including substantial amounts of organized crime, it was repealed with the ratification of the 21st amendment in 1933.

As a form of checks and balances, lawmakers created a three-tier system to protect the consumer and ensure revenue from tax collection.

| The three-tier system | |

| Tier 1 | Suppliers can be U.S. producers or importers; they provide products to wholesalers and retailers and can also sell directly to consumers |

| Tier 2 | Wholesalers distribute products to retailers |

| Tier 3 | Retailers sell alcoholic beverages directly to consumers (bars, grocery stores, restaurants, liquor stores) |

Suppliers and retailers were already a part of the ecosystem. A new middle tier — wholesalers — was established to create a go-between, or separation, between the suppliers and retailers. Within this traditional three-tier system, suppliers provide their products to wholesalers, who distribute to retailers, who then sell to consumers. To prevent influence between tiers, restrictions are enforced on ownership and involvement across tiers.

In a modified version of the three-tier system, there are 17 states and a few jurisdictions that control the sale of distilled spirits, and in some cases wine and beer, through government agencies at the wholesale level. Some of those states also have control over retail sales for off-premises consumption. These areas are referred to as control states. A map and list of these states can be found here.

Compliance requirements for beverage alcohol suppliers

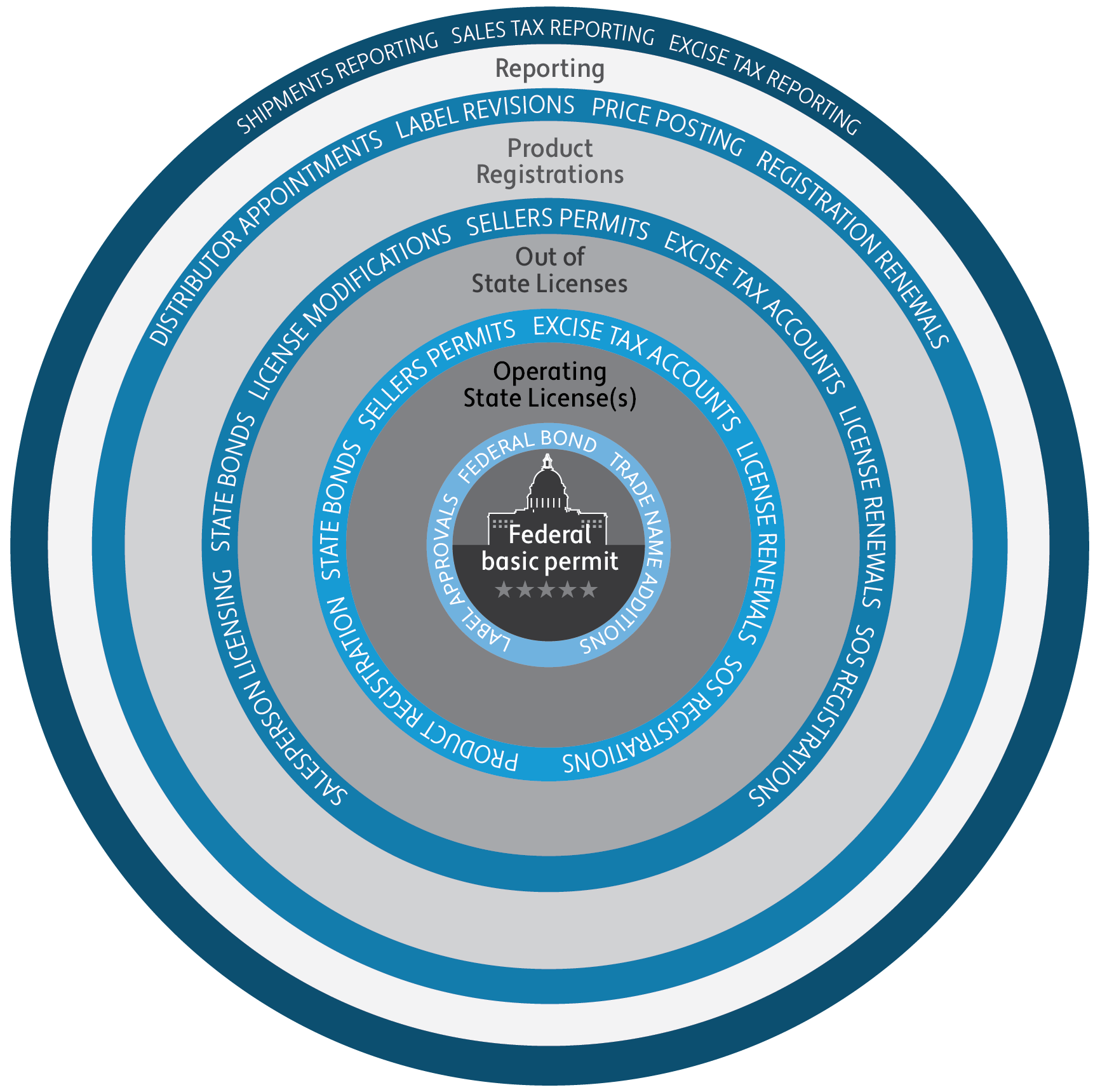

Whether just getting started in the business, expanding into new states, adding labels, or just brushing up on the details, there are several critical requirements every beverage alcohol supplier in the U.S. should fully understand. The graphic below illustrates this complexity — and the steps you may need to take to remain compliant.

Federal and operating state establishment

When establishing a business as an alcohol supplier, federal permitting from the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) is the first step. TTB regulates licensees as part of the powers established in the Federal Alcohol Administration Act. It regulates alcohol production, labeling, advertising, importation, and wholesale/exportation businesses.

After getting a federal TTB permit, the next step is obtaining a state license from the state where you’re supplying alcohol. Any local jurisdiction permits and licenses must also be secured and approved.

After these licenses are obtained, suppliers are now able to conduct business within their operating state(s). They’re also obligated to pay federal and state excise taxes and to provide ongoing reporting to TTB, as required by their permit type.

Out-of-state licensing

Once the supplier is licensed federally and with their own state they can begin the process of acquiring out-of-state licenses. The majority of states have licensing requirements for “non-resident dealers,” i.e., suppliers not located within that state. The licensing process involves some or all of the following steps:

- Secretary of State registration

- Bonds

- Tax permits

- Excise tax accounts

- Bottle recycling program registration

While Secretary of State registrations and tax permits don’t typically expire, bonds, direct shipping licenses, and non-resident dealer licenses (commonly referred to as wholesale) do require renewal and maintenance.

License modifications to report changes

A commonly overlooked area of compliance is license modifications. Most licenses include regulatory stipulations requiring notification to the licensing agency when important information changes. This may include:

- Legal name

- DBA (operating name)

- Mailing address

- Premises address

- Changes in ownership

Changes in ownership are especially important as these can potentially violate federal or state tied-house laws. When considering new investors or a change in ownership, it’s always advisable to consult a beverage alcohol expert and ensure that investing parties are eligible for ownership. Otherwise, you may face fines or a forced termination of the business due to a tied-house violation.

A tied-house is described as a retailer that’s beholden to a particular alcohol supplier. Before Prohibition and the three-tier system, large alcohol suppliers were able to negotiate favorable or monopolistic treatment from retailers. This removal of competition and consumer choice provided retailers an incentive to oversell alcohol made by their benefactor. The Federal Alcohol Administration (FAA) Act establishes trade practice rules and regulations to prevent this unfair advantage and protect consumers.

Registering products

Once the supplier has the proper operating permits and produces or purchases products, those products must be registered in some states. There are generally two steps to product registration:

- Federal registration. Each new product must be tied to a Certificate of Label Approval (COLA) from TTB, unless the products are less than 7% alcohol by volume. Some products will also need formula approval in order to secure a COLA.

- State-by-state registration. After the COLA is approved, products must be registered with each specific state ABC where they will be sold, if the state requires registration. Specific requirements and limitations vary from state to state.

Updating registrations

Product registration should be considered an ongoing task for suppliers; products need to be registered and continually updated with both TTB and the destination state Alcohol Beverage Control (ABC) agency. Once a product is registered, changes made to the product or its packaging need to be evaluated to determine whether an update is required for certain jurisdictions. Some changes to labels require an entirely new registration, while others are deemed allowable revisions.

Requirements for products distributed as a non-resident dealer (NRD) vs. direct to consumer (DTC) also often differ. Some states even require separate registrations. The same is true for variances by state. The owner of the registration is responsible for knowing when updates are required.

Reporting and returns

Once all permits, licenses, and product registrations are in place, suppliers are responsible for reporting and returns at several levels. If the operation produces beverage alcohol, federal and state production reporting is required along with excise tax returns.

For interstate commerce, suppliers may also be required to submit a list of invoices for products they’ve sold to wholesalers as a non-resident dealer.

Similarly, direct to consumer licensees typically must pay both excise and sales taxes. They may also be required to submit a direct shipping report to each state in which they’re licensed, including a list of sales invoices for each destination state.

A growing trend among state ABC agencies is to compare the supplier reports to reports they receive from common carriers, like FedEx and UPS, as well as fulfillment houses. They look for discrepancies between the direct to consumer licensee, carriers, and fulfillment houses to verify the correct excise tax was paid and the shipping entity was licensed to make the shipments.

Understanding different tax types

A number of different tax types are applied to beverage alcohol, and at different times in the supply chain. Each has complexities, but all are important to understand in order to achieve accuracy and minimize audit exposure.

Federal excise tax

Excise taxes are due on most beverage alcohol products produced in or imported into the U.S. Excise taxes aren’t exclusive to the beverage alcohol industry and are also collected from the sale of motor fuel, airline tickets, tobacco, communications, health-related goods and services, and other restricted commodities. These taxes aren’t paid directly by the consumer but are instead baked into the price of a product or service. Federal excise tax is due to TTB on all beverage alcohol products above 7% ABV, but the specific alcohol type, ABV percentage, and total volume removed during the calendar year determine the amount due by volume.

Understanding when this tax is incurred is important. In the case of producers, products are often bottled, labeled, then put into storage “in bond” so payment of taxes can be deferred until products are ready for sale. Some fulfillment facilities provide bonded storage for producers, allowing that facility to pay the excise taxes directly upon shipment then bill back the supplier. Whether the supplier stores their own inventory or uses a third-party warehouse, the federal excise taxes must be paid before sale to consumers or wholesalers. This is an extremely important component of record keeping all producers should mind closely. Importers should also be mindful of their excise tax responsibilities, strategy, and record keeping.

State excise tax

Like federal excise tax, state excise taxes are paid on specific goods and aren’t charged directly to the consumer. Instead, they’re included in the total cost of producing the product.

State excise taxes can differ depending on their application to a DTC seller or a non-resident dealer. For example, if a winery is selling directly to a consumer, they’ll typically pay the state excise tax. These taxes apply to all direct shippers in the state where excise taxes are applicable. Conversely, during non-resident dealer distribution (or self-distribution by a producer), state excise taxes are rarely paid by the supplier when selling directly to a retailer.

Sales tax

Most states require sales tax be paid if a supplier is located within a state or shipping to a state that allows DTC shipping. The only states that don’t require sales tax are New Hampshire, Oregon, Montana, Alaska, and Delaware (often referred to as the NOMAD states.) If the state is not a NOMAD state, whether you have to pay sales tax or not depends on that state's nexus laws and the laws that govern DTC shipping.

Nexus laws include a sales tax obligation based on a certain level of economic activity within the state, including sales revenue, transaction volume, or a combination of both. Like many sales tax laws, economic nexus criteria vary by state and by the type of tax.

Markup taxes

Markup taxes can be tricky — they aren’t a tax on the actual product, but a tax on the retail value of the product. The “retail value” distinction is important because even when a product is sold at a reduced price, for example, a $100 bottle of wine sold for a discount at $80, the tax should still be paid on the original value of $100.

This tax type is a hybrid of excise tax and sales tax and is required by a handful of states. Suppliers pay markup taxes in those states if they have a direct shipping license.

The beverage alcohol compliance bottom line

Achieving — and maintaining — compliance is complicated. There’s no way around that. However, if you follow the guidelines above — acquire permits and licenses, pay your taxes, and file the proper reports and returns — your business should be well on the road to compliance.

But, since compliance isn’t a one-time task, compliance maintenance is critical. Both small and large changes can trigger a need to update compliance: expanding into new states, changing formulas, updated state laws, new business ownership, etc. Staying on top of and up to date on the rules is a must.

Fortunately, companies like Avalara have the expertise and the staff to help. We have services to support a compliant business, including a dedicated software platform and experienced industry consultants.

Contact the Beverage Alcohol team at Avalara to find out how a compliance partner can support your business.

Avalara is dedicated to simplifying tax and regulatory compliance with easy-to-use software and helpful service designed specifically for the beverage alcohol industry. We can help you spend less time worrying about tax payments, license filings, and state and federal regulations — and more time growing your business.